The Fine Line Between Being Different and Crazy [Part 2]

Lower middle market private equity reimagined

[This is Part 2 of a two part piece. Please find Part 1 here if you want to understand how we got to this point.]

Before I get into the details of the strategy, I should note that this piece is not a solicitation of any sort. It is simply a philosophical discussion surrounding the strategy my team and I are starting to actualize.

With that out of the way, I should warn you, dear reader, that article is going to run long. In fact, if you are reading this in your email, Substack has alerted me that you will need to click “View entire message” to read the whole thing. It represents the culmination of many, many hours of conversations, a deep exploration of potential pitfalls, another lengthy listening tour, and a lot of brainstorming within the team. Here is the summary and TL;DR version for people who want the punchline.

There is a structural lack of growth capital available to microcap companies in the US, a dynamic that has been exacerbated by a number of factors, including the poor relative performance of microcap (versus everything larger cap), the slow disappearance of the sell-side, and the attrition of the buy-side investors who focus on this space. On top of that, as the costs of being public have continued to rise, there exist an increasing number of companies that, especially if being listed doesn’t provide ready access to capital, have no reason to be public anymore.

Many people are aware of this and the fact that a lack of price discovery can often lead to inefficiently valued securities. However, the public investors in the space run capacity constrained strategies and may not have the necessary skill set, desire or proper investor base to make large investments (i.e. write $25mm+ checks) in individual companies to take advantage of the gap between stock prices and intrinsic value or to provide companies with growth equity.

Lower middle market private equity (PE) firms, outside of some recent activity north of the border, appear to spend the majority of their time looking for private-to-private deals. Why? Negotiating with the owner of a private industrial business who wants to sell is much easier than is dealing with outside shareholders as well as entrenched Boards and CEOs who may not want to give up their paychecks. Additionally, many PE funds are not set up to buy 20% of a public company and then wait 2 years to make an offer for the rest. Our extensive research has yielded the hypothesis that to be successful, anyone interested in executing take-privates has to have a flexible mandate and be able to navigate the idiosyncrasies associated with sourcing and owning the shares of small public companies.

All of the above creates an evergreen opportunity for a team with diverse skill sets that include both public market and private market experience to employ a private equity in public markets strategy that can: 1) take large stakes—either control or non-control—in public microcap companies or 2) execute microcap take-privates. We strive to write big checks in a space with a structural lack of capital and to add value to the companies we invest in via operational improvements as well as implementing best practices as it relates to corporate governance, capital allocation and compensation. Some people may argue that there are no compounders in microcap—that all of these companies are fatally flawed. However, our diligence suggests that in many cases, it is the structural lack of patient capital that is hindering faster compounding.

This strategy can scale and eventually attract institutional investors who have stayed away from microcap because of the inability to put a lot of capital to work in public equity strategies. For sure, in order to generate the best returns, we would limit the size of any individual fund and the total asset base. But, whether we are writing $30mm or $125mm equity checks to close deals, the strategy can deploy enough capital to be meaningful to investors and to allow us to build a sustainable business. However, in the beginning we will most likely start with single deal SPVs as we aim to build a track record and prove to the outside world that this strategy has repeatable elements.

With all that in mind, I have joined my long-time friend Shahzad Khan at Devonshire Partners. We have assembled a diverse team of people (a few of which we have yet to announce) and created a thoughtful, flexible structure that is specifically designed to avoid some of the pitfalls that have caused others who attempted something like this to not be as successful as they had hoped. Paraphrasing a quote from a famous value investor who just passed on, we know where other strategies went to die and it is our intention not to ever go there.

Where this Idea Came From

Anyone who hears about what we are doing can quickly grasp the the hypothetical applications of the strategy. It is easy to put together a compelling PowerPoint presentation (indeed we have) about the philosophy, opportunity, and why so few other people are pursuing this path. But the question that inevitably comes up is: is the opportunity real or is this yet another group dreaming about the seemingly amazing—but ultimately elusive—returns available via diving deep into microcap land? My response to that question is that I know it is real because I have lived it. I spent 12 years at a firm focused on small and microcap companies and during my last 2 years at Cove Street, I saw two distinct opportunities to write big checks that are illustrative of why we have so much conviction in the strategy.

In the first situation, we had a strong relationship with the CEO of a company that was controlled by a family. (He was even on Compounders.) We owned a fair amount of stock and one day we got a call from the CEO who said that the patriarch of the family was ill and wanted to sell his large stake in the company. The CEO also said that he wanted the shares to fall into the hands of someone he knew and trusted—and therefore they were willing to give us an exclusive period to try to raise the money to buy the shares. For the next few months, the Cove Street team spent countless hours trying to raise over $200mm to buy this stake at a very reasonable, pre-negotiated price per share around $27. Unfortunately, the issue was that we were just not set up to be successful. We were a long-only firm with allocator partners who were not “alt” people and the check size was substantial relative to our AUM. While we were ultimately unable to raise the capital, the benefit of having a structure that would allow an investment firm to own 30% of a public company—sourced via an intimate and exclusive relationship with management—was seared into my brain when the company was acquired for $45+ not very long after. While this company was bigger than the ones we are focusing on, my sense is that given the lack of liquidity and the poor recent performance of microcap stocks, situations like these are bound to be even more prevalent in the sub-$250mm market cap range.

In the other situation, a PE sponsor was in the 11th year of a 7-year fund and was gradually selling down its stake in a small cap company we owned. Every time the stock hit ~$11, the PE firm would do a secondary at $8 or lower—crushing the stock of course—and then would wait 180 days to do it again. Through the company, we got in touch with the PE firm who said that they would be happy to sell us all of their stock for $8. Again, we were not set up to write a multi-hundred million dollar check but the experience of watching an uneconomic seller punish the other shareholders with consistent secondaries was illustrative of a broader opportunity to create a firm and structure that would allow a group of investors to take advantage of other investors’ desire for liquidity. The strategy has evolved to include other ways to put capital to work but these two experiences were formative.

Why Microcap and Why Now?

I am a contrarian by nature and am intrigued by the proposition of going to places where other investors have abandoned or are afraid to venture—or both. Microcap in many ways is a dirty word to a lot of investors and institutions. The perception is that the space is populated by unscrupulous management teams, perpetually money-losing companies and structurally flawed business models that have become un-investable, especially when compared to much sexier SaaS and AI companies. If you look at the recent returns generated by microcaps, it would be easy to conclude that no one should spend their time searching for diamonds in the rough in the space.

For example, the above chart—sourced from Russell’s website—contains the returns for the various Russell indices that are focused on US stocks. If you look right in the middle of the chart, you can see that the Microcap index is the worst performing one over EVERY SINGLE long time horizon. However, there is plenty of data that indicates the current period is an historical anomaly. It is hard to get data on microcaps specifically (remember, almost no one cares about this space) but I feel comfortable using small caps as a decent proxy for microcaps. This chart highlights the degree to which small caps have swung from trading at a premium to larger cap stocks to now trading at discount not seen since the tech boom.

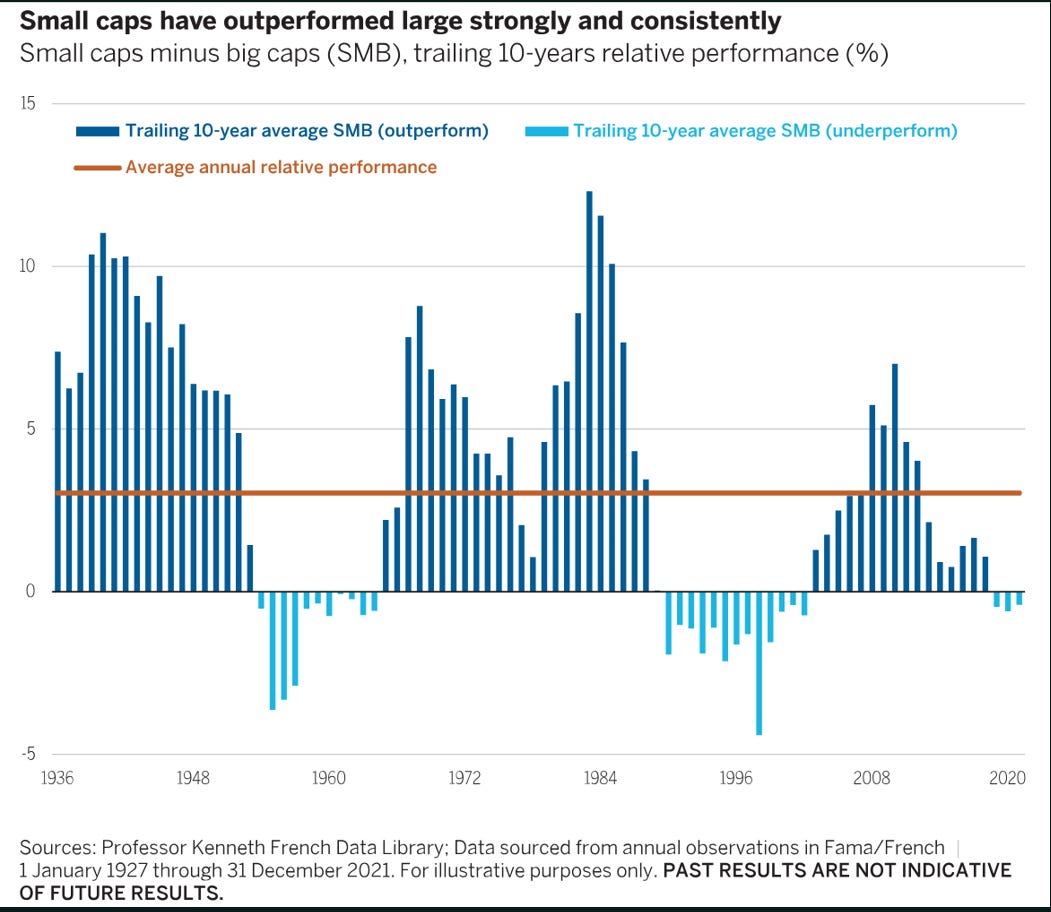

Furthermore, while it may be hard to remember, given the recent performance of the S&P 500 and the Mag-7, small caps have traditionally outperformed large caps over time. As this chart shows, we are currently living in one of the rare periods where smaller companies’ returns have underperformed those of their larger brethren.

These charts are helpful in establishing the philosophical basis for why there could be an opportunity to unearth underpriced, misunderstood small and microcap companies. They also help answer the “why now” question that is always important when trying to convince other people to fund a strategy. But aren’t all of these companies “small for a reason” and isn’t investing in microcap basically akin to adverse selection where you are only sifting through the garbage bin of public companies? Well, if you filter out the non-earners (which are easy to avoid), what you see in the Russell chart included below is a group of companies that generate respectable earnings growth but that trade at a fraction of the multiple that the larger companies currently go for.

Target Universe and Investment Criteria

As we are attempting to build a track record, we have decided to focus on companies listed in the US and Canada with market caps of $5mm on the very low end to $125mm on the high end. We wanted to have a pretty broad universe to start and thus, aside from using some industry filters to screen out banks, utilities and energy companies, we simply put two initial constraints on the companies: gross margins above 20% and EBITDA greater than zero (historically profitability is a must have). As shown below in a screen from CapIQ, that takes the universe down from ~1700 companies to about 180 companies.

Given my evolution to focus more on quality and less on stated multiples, everything we look at is going to be put through a quality lens. We plan to be very picky about the types of businesses we want to get involved in. I have made the mistake too many times before of investing in mediocre or secular declining businesses and our process is designed specifically to avoid such situations. So, what are we looking for?

•Factors we have to see: limited customer concentration, businesses that have a reason to exist (even if they are small), somewhat predictable cash flows, low leverage, capital light business models, roll-up and re-investment opportunities, companies that play in the most profitable part of the value chain, blue chip customer bases, and recurring revenue bases

•What we plan to avoid: heavy cyclicality, price-taking or unproven business models, binary risks, promotional management teams, limited cash flow generation, “story” stocks, silver bullet solution situations, turnarounds, and secular pressures on revenue/margins

Our research suggests there are plenty of quality companies in this market cap range, many of which trade at reasonable valuations, especially relative to the 11.4x average EBITDA multiple that Pitchbook calculates PE firms paid for middle market deals in 2023.

Core Principles

In my experience, investment firms with great cultures have very specific principles that are followed consistently across team members and across time. While we reserve the right to change and evolve as a firm and to see these principles evolve with us, below is a list of the principles we plan to live by as we execute this strategy.

1. We don't win unless our clients win—and we never forget that.

2. Every action we take starts with a win-win, partnership-first orientation. There are a lot of players in microcap land who exist to take advantage of small companies. We will be the antithesis of that.

3. We are doing this not simply for the financial reward but also for the joy of learning about new businesses. We will stop if the process ever ceases to be fun.

4. The capital in a transaction is a commodity. Relationships are not. We will win and lose based on our relationships and our ability to serve as a bridge between different players in the ecosystem.

5. While not guaranteed, success can come from doing things other people deem too hard or not worth their time. With that as a backdrop, we will make mistakes along the way, but they will never come from lack of effort or focus.

6. We will not hesitate to refuse to work with companies or other partners who do not share our vision and principles.

7. There is a wide open and evergreen opportunity to build a premium brand in the microcap space, one that starts with the premise that there exist real businesses that have been neglected by other market constituents.

8. There is still room in this lawyer-dominated world for handshake deals between constituents and partners. But we reserve the right to act forcefully in order to protect our LPs and companies.

9. Size is the enemy of success. We aim never to get too big to be unable to fund a company in our original investment universe.

10. No matter what people say about the availability of capital, good deals get funded. We have that phrase tattooed on our foreheads.

Multiple Ways to Win

Let’s say you are on board with the concept, philosophy and the potential return attributes of this strategy. But if it is so compelling, why aren’t more people doing it? Why have so many public managers who had the ambition to execute take-privates not been able to be consistently successful? Aren’t the established middle market PE firms far better suited to execute this strategy than is a group that is just starting out? My hope is that I can provide satisfactory answers to these questions throughout the rest of this piece. However, I want to start off with the most concise articulation of the strategy possible and then make sure to address the concerns and feedback we consistently hear.

Flexibility is a core tenet of the strategy and the manifestation of that is tied to having multiple paths to deploying capital and various ways to win.

Path 1

Acquire large stakes in businesses that we would like to own entirely via a PIPE that is tied to specific growth initiatives or by buying a stake from selling founders, shareholders, or families (similar to the situations described above)

Via board membership, partner with management to improve corporate governance, operations, compensation and capital allocation

If shares go up, clients benefit, and we build a track record of success

Liquidity improves as valuation increases

Be in position to encourage the company to seek strategic alternatives, but only if it is truly warranted (i.e. things are going really well and there is an acquirer who is a better owner of the company or things are going very poorly and a sale is determined to be the best way to protect our investors)

If the take-private opportunity is very compelling (see conditions below), make a bid for the whole company

Cut public company costs and facilitate growth outside of the public view

History as an insider makes us a better buyer because we know the business inside and out

If we already owned 20% of the company, for example, we would then only need to pay a control premium for the other 80%

In this scenario, we aim to establish influence or even near-control without paying a control premium initially. The idea is to use our influence and our standing as a large shareholder to encourage management and the Board to think and act longer term, to ignore the quarterly earnings and sell-side upgrade/downgrade noise, to deeply embed a return on capital framework as the company’s capital allocation North Star, and to make sure that executives’ comp is highly aligned with the key variables that are going to drive value creation for shareholders over time. We don’t require outright control to get involved because our goal is to enhance what is already working at these companies. Given my long background as a public equity investor, I would be thrilled to watch a business compound for years (tax-free) as a public company. But that doesn’t mean we will be passive holders of our stake. I would foresee very little difference in terms of our level of involvement whether we owned 20% or 100% of a company.

Further, we would only aim to execute a take private—and pay a control premium—if:

The public company cost burden was so high that it was strangling growth.

The company has high return investments that are either challenging to make as a public company whose quarterly results are over-scrutinized or impossible due to the lack of available capital. In that scenario, we would look to provide additional growth capital in the private setting.

Management and the Board determine that there is something about the business model that is highly unlikely to ever be fully appreciated by the market. I often talk about companies that are “bad" public companies. What that typically means is that they either have lumpy or hard to predict cash flows. They aren’t bad companies in the slightest. They just have trouble playing the guidance and earnings expectations game. I would rather have a lumpy 15% return than a 12% straight line return. But, in the public market, that 12% returner might get a better valuation than the one with a higher return potential because volatility equals risk in some people’s minds.

The discount to our perception of intrinsic value became so extreme that even with paying a healthy premium, we could achieve mid-20s IRRs in our most conservative base case.

We philosophically like to be involved only if there are win-win scenarios available and a stock that generates great returns benefits us, existing shareholders, employees and management. We can be flexible and don’t need to take such a company private.

Path 2

Identify management teams who no longer see the benefit of being public, especially those who believe they have high return re-investment opportunities but are unable to tap the markets for capital due to possessing a perpetually depressed currency

Educate them about the benefits of being PE-backed executives, as well as the cost savings

Propose the idea of a management-led buyout

Management buy-in reduces information asymmetry and misaligned incentive risks

Given years’ worth of historical financials, conference calls, etc., we can be incredibly informed before going into a data room

Acquire the company for a fair price, cut public company costs and be in the position to ride the coattails of excellent management teams

Become deeply knowledgeable about and involved with the company in order to advise on operations, capital allocation, governance and compensation

Be in position to provide additional capital for M&A or high return capital investments

Multiple exit paths available:

IPO, hopefully as a larger company that can receive a higher valuation

Sell to a strategic who can realize synergies in the transaction

Sell to a sponsor who wants to build upon the platform we have developed

Or, if our investors are family offices or endowments with a very long time horizon, hang onto a compounder for far longer than a traditional PE fund typically can

I should mention here that we are explicitly seeking situations in which the companies are not officially for sale or looking at strategic alternatives. We have no edge and our value proposition is limited in a banker-led auction. Alternatively, like in the situations described above, we want—via a relationship—to get the first look at a block of stock that has not been shopped widely. The allure of lower middle market PE is the exclusivity of deals that come about due to deep relationships with business owners. We are trying to replicate that in public markets under the premise that there is limited competition. Specifically, I believe there are something like 6000 private equity funds in the US now. There are certainly not that many funds focused on microcaps. Also, it is my experience that most small companies have to give up an arm and a leg to raise capital. There is certainly not a line of potential suitors waiting outside of their doors, and that dynamic gives us the chance to establish at least a semi-exclusive relationship to start.

Why Would Management Partner with Us?

While we require a clear path to influence or control when we make an investment, we philosophically want to invest in companies where we would be happy owning 1% of passively—because the business is already growing and operating well. In those cases, the improvements we can catalyze only amplify the returns to our investors. This is a differentiated approach in the space where many people are looking for turnarounds, new management stories and dirt-cheap but flawed stocks. We will no doubt have to prove ourselves in this capacity but we have assembled a seasoned team of highly active advisors and partners who have decades of experience navigating the public markets, helping companies improve, and with building relationships with management teams and Boards.

We are also solving the structural lack of growth equity problem. In a very tangible way, we are helping them navigate financial markets. That is a major value-add for companies that don't have easy access to equity capital. It may not be sufficient by itself but the combination of that and everything else above represents how we are adding unique value. Plus, by providing these companies access to growth capital we can help the business reach levels of growth and profitability that would have been otherwise unable to achieve. Specifically, by having the ability to provide growth equity—via PIPEs or additional capital in a private setting—to companies to invest in their business, we generate returns by helping them become more valuable over time, as opposed to primarily using financial engineering and special dividends to generate returns.

In our experience, almost nobody is coming to these companies offering to help them grow without putting onerous terms on them or extracting exorbitant fees for helping them raise capital. The early response of this approach have been very positive and we are already establishing relationships that are very different from the ones I had with management teams when I was a public company investor only. Every day were are working to increase the sample size so that we can better understand the probability our approach will be well received by all constituents. But anecdotally, what we hear from CEOs is that this is the best time in their careers to be trying to execute this strategy within microcap.

Start with the premise of an MBO

The M.O. of stereotypical PE firm is to lever a company to the hilt and then replace management, fire a bunch of employees, juice the margins by cutting off growth investments, and start prepping the company to be sold after just a few years. While I think that is an accurate description of some firms, the reality is that many firms run a different playbook. But the specter of the aggressive PE firm certainly hangs over any situation where established PE firms get involved. We aim to distinguish ourselves by only getting involved in situations where the goal is to keep a good-to-great management team in place and to encourage management and the Board to roll their equity in the private entity. I would even go as far as to say we will abandon any process in which we start to believe that management isn’t aligned with us or doesn’t have the requisite technical and personal skills to take the company to the next level.

Within that, we have created some ground rules that we plan to share with the companies that are willing to engage with us:

1. We only go into situations where we can foresee a lasting partnership and win-win outcome for the company and Devonshire.

2. We only engage with companies we would like to invest in personally and would expect to be involved with for a minimum of 5 years.

3. We only approach management teams our diligence suggests have a high degree of integrity.

4. We are never trying to steal companies from public markets and investors. In a take-private, we seek to pay a good price for a solid business and to allow compounding to widen our margin of safety. With companies that will remain public, we have no interest in creating onerous securities that strangle the company. There are already too many predatory and “loan to own” players in the microcap space.

5. Leverage is a tool in our toolbox—but it is not the only tool—and we will use it judiciously.

6. A valuable partner comes with solutions that are specific to the company. We are not going to fit a round peg into a square hole. It is our job to come up with the right financing and capital solution, and if we can’t, we will happily let someone else do it.

7. The best outcome possible is for management to be fully bought into our solution and for the team to be financially aligned with Devonshire.

8. We have a seasoned team and we can execute a diligence process quickly. A fast close is also something we strive for in every situation.

9. Our job is not to tell anyone how to run their business. We want to be supportive and use our experience in operations, capital markets, governance, incentive alignment and capital allocation to help a business thrive. But, if we don’t believe our collective skill sets and experiences can lead to meaningful improvements over time, we will refrain from engaging. For every deal, we ask ourselves, “why are we good owners of this business?” If we don’t have a well-researched answer that includes a detailed plan of action, we will pass.

10. Another aspect of our role is to serve as an active bridge between our company partners and the other constituents who can be helpful, including customers, capital providers, industry experts, Board Members, and potential employees.

We aim to become the partner of choice for management teams, Boards and companies that are looking for long-term oriented partners who are willing to make large investments to help facilitate compounding. That is a big, hairy, audacious goal (BHAG) for a new firm but our experience in the microcap space suggests there is a glaring lack of partner-oriented suggestivists, investors willing to write large checks and people who seek to help companies as opposed to prey on them.

The Three-Sided Market

I have put a lot of thought into what relationships we need to establish to give us the best shot at being successful. What I have landed on is a three-side market that we need to continuously be cultivating.

Public company microcap investors: I am lucky enough to have a network of investors all around the world who have been introducing me to the most accomplished US and Canadian microcap investors. The pink elephant in the room is that I am asking people to share ideas that fit our criteria with us, fully knowing that at some point we could be at odds if we try to buy one of their companies. To my pleasant surprise, we have been receiving consistent inbound from microcap investors who come across ideas they think we might be interested in. What I have gleaned is that for most investors there is probably 20% of their book they would be really upset if we bought from them. With the other 80%, assuming they got a decent premium and some immediate liquidity (the value of which should not be underestimated), they are fine with letting them go and then looking for the next investment. There is no scarcity of interesting stocks in microcap. We hope that these experienced, savvy investors will be an ongoing source for ideas and warm intros to companies.

Family offices: A requirement to be successful in any new business endeavor is to understand the potential customer base. When I interviewed Nick King, the founder of Vint, for the podcast, he mentioned that if he was starting the company again, he would not write a business plan. He would do 100 potential customer interviews instead. That is the path I have been on recently and it has become abundantly clear that our strategy is not institutional caliber yet. We don’t have a 3-year track record for anyone to audit. (Not many people do—if any—by the way.) As such, our current target client base consists of medium-sized family offices who are interested in seeing “deal flow.” What I have heard consistently is that almost nobody approaches these family offices to invest in a microcap take-private. They tell me they see private deals all day and all night but that there is essentially no such thing as an independent sponsor focused on the public side of lower middle market PE. The differentiation of our holistic approach is certainly not sufficient to get people to back us. But it definitely helps in getting our feet in the door.

Microcap management teams: For any of this to work, we need to be able to convince management teams that we will be good partners. Even if the other two sides of the market are functioning superbly, without willing management teams who understand the logic—both financially and personally—of what we are proposing, we will never be able to make an investment. As mentioned above, everyone we talk to gets what we are doing. Being a microcap CEO over the last 5 years has been, for the most part, distinctly un-glamourous. If a stock is down over 5 years despite solid execution, people start to wonder if the market will ever appreciate their efforts. We believe it goes a long way to tell executives that our goal is to provide them with capital to build their businesses over a multi-year time horizon. But we still must be both credible and trustworthy in eyes of the Board and management, a lot of which will emanate from having good relationships with other microcap investors and family offices. The way we ingratiate ourselves with management is to do exactly what we say we are going to do and to be incredibly informed and curious about the companies we speak with. This is another facet of our approach that is necessary but not sufficient. What we lack in terms of track record we aim to make up for with hard work, deep diligence, and a high EQ approach.

Avoiding Landmines

An interesting outcome of the listening tour I have been on regarding this microcap strategy is that I have heard lot of stories about people trying to do something like it. It even turns out that a lot of people I know or have been introduced to have had a similar idea. However, very few people have been able to execute well. There is a firm called Mill Road that has been pursuing a consumer-company-focused version of this strategy for years. Plus, the guys at Privet Fund closed a deal. But for every firm that has been able to make the leap from public to private, or that is employing a hybrid strategy like ours, it appears that there are probably 10 that have not been to do so. The most common feedback I get from microcap investors and family offices is that this is a wonderful strategy on paper—it is just extremely hard to execute in practice. Like with all investment strategies, implementation and execution are paramount. We will only know over time if we can defy the base rates and succeed where others have struggled. What we have done though, is designed the strategy to avoid some of the pitfalls we have witnessed impact others. After a fair amount of research and a large number of conversations, we have distilled the information down to the following common lessons:

Apply a non-negotiable quality filter

Quality is obviously in the eye of the beholder when it comes to companies, and it embodies everything from business model to competitive position to culture. We are starting off with the premise that we will not act until we find a company for which we see quality elements in ALL facets of the company, especially when it comes to management. In terms of business model, I listed a bunch of factors above that we are looking for. Not every company can satisfy all of them but we will need to see many of those represented in order for us to be genuinely interested.

Aside from the fact that I have personally lost money in business that do not exhibit those traits—and that often combined a bunch of negative traits such as leverage, cyclicality and secular headwinds—I have also watched other investors employ an activist-style approach in microcap whereby they look for companies with problems: bad management, poor execution, cheap stocks with secular headwinds, turnarounds, or companies with very complicated or stressed capital structures. The problem with that strategy in our opinion is that it is often focused too much on buying something cheaply and that, when things inevitably go wrong (because you know they will at some point), the margin of safety is quickly eroded.

We would rather not swing at all than bet the house that a business with some fundamental problem is not going to have an internal hiccup or a negative exogenous event during the period when we own it. In line with that thinking, this strategy will explicitly not lever a company five times just to write the skinniest equity check possible. In an environment where rates are as high as they are now, we see that as a good recipe to lose investors’ capital and never do a deal again. This is a growth equity strategy focused on management-led buyouts. We will leave the levering and financial engineering of cash-flow-generating but hard to predict businesses to other investors.

This is a long way of saying that security selection matters more than anything else and thus we will aim to partner with companies that are getting more valuable over time and exhibit positive internal business momentum.

This is a full-time job

What we are proposing to do is not a side gig. We don’t believe most firms can run a 20 to 100 stock long-only or long-short fund for existing investors and be excellent at sourcing and closing deals—or at building businesses in a private setting. Our premise is that the skill sets associated with managing a microcap strategy are highly valuable but that they are not that transferrable unless an investor decides to pursue this control/near-control strategy full time. Helping small companies grow is an endeavor that requires the team to be pseudo employees of the company. It requires deep engagement from both a risk management and a business development perspective. It is REALLY hard to do that and provide good client service for existing LPs, continue growing your public AUM, and beat a chosen index.

There is a big difference between taking a 3% passive position and buying 100% of a public company. You have to be willing to travel and get your hands dirty. Most public investors don’t have a lot of experience doing that and, as Cove Street found out over a number of occasions, just being an activist in a stock takes an enormous amount of time. In my experience, without any question the time commitment forces you to reduce the time you spend on the rest of the portfolio. As such, if you have a small team, corners have to be cut. My guess is that you can magnify that by 5x if you have control of a company, public or private. Our team is focused executing on this strategy and any investments we make in public companies will be with an eye towards control.

Thinking about it the other way, a lower middle market PE firm that spends 10% of its time looking for deals in nanocap is likely going to be a tourist in the space. To be really successful, our hypothesis is that you have to live and breathe public companies and potentially develop relationships that take years to manifest in a large investment. That is also true in the private-to-private world. But if I saw actionable private deals where there was potentially one decision maker between me and a transaction, the opportunity cost of spending time in microcap would be quite high, especially as you layer in the different skill set required to navigate public markets. In order to get a position, Devonshire might just have to tender for shares, source illiquid stock via pre-negotiated large blocks, and develop relationships with the other microcap investors who own the stock. We may have to put someone on the Board and file some 13-Ds. Of course there are smart and capable people at these lower middle market PE firms who could learn the ropes. I am just making the point that we have the suggestivist and public company skills on the team already, in addition to experience sourcing and closing private deals.

Flexibility is an absolute necessity

This has been discussed above so there is no need to belabor this point. Our sense is that a strategy that has too specific or narrow a mandate that it cannot deviate from is going to struggle to be successful. Accordingly, we are willing to do what it takes to defy the base rates, including:

Acquiring large public stakes and holding them for years, even if a take-private is not on the table on day one

Putting people on the Board of a public company in order to influence the direction of the company

Buying large blocks from selling shareholders even if we can’t own 51%

Allowing existing shareholders to roll into a private deal

Partnering with a lower middle market PE firm to get a deal done

Raising capital for a growth equity PIPE

Holding a company for longer than a traditional PE fund life allows for if our investors prefer to compound tax free

Every deal is going to be different and if all you have is one way you can invest—buying 100% of a public company, for example—you are likely to miss out on a bunch of compelling opportunities or simply never get a deal done.

Don’t try to be the next Berkshire

The dream of many value investors is to emulate what Munger and Buffett accomplished and get control of a public company. The idea is, if you can just get your hands on permanent capital in the form of a public company and compound at 15% for 30 years, you can build the next Berkshire. What could be easier? The reality is that the average hedge fund manager who thought he or she could run a public company or got his or her hands on a public NOL shell has not been able to come close replicating what Berkshire has done. The companies and people who have had success are the outliers—the survivors. While we are intrigued by alignment and the tax advantages associated with public holding companies, our goal is not to try to use this strategy to build a mini-conglomerate. Instead, the objective of our intended structure, which is inspired by that of my friend Soo Chuen Tan, is to compound tax-free for as long as possible and not be constrained by having to start marketing a company for sale three years after we bought it—just to make sure we have an exit by year seven. We believe that approach, when combined with modest management fees (especially in total dollar terms) and performance fees over a preferred return, offers proper enough alignment.

The Path Forward

Everywhere I look, I see chicken and egg problems that are tough to solve without the passage of time. We will need to find compelling companies with interested management teams and then approach our network of family offices in hopes they will support the strategy and the specific investment opportunity by backing a group of emerging private equity managers. Fortunately, we currently have a pipeline of companies that check a lot of our quality boxes and have management teams who get what we are doing. Our approach is already working on many levels.

As I mentioned in the piece from last week, I am keenly aware of the base rates of success and just how hard this is likely to be. However, I firmly believe that the combination of the structure, philosophy, approach, differentiation and risk mitigants described throughout this article is enough for us to distinguish ourselves, given a long enough runway. What I know for certain is that I am having as much fun as I have had in years and that alone is sufficient to keep pushing me forward.

If anyone is interested in helping the cause, the best thing you can do is share this article with anyone in your network for whom you think it will resonate. The Devonshire teams is all about continuous improvement and therefore we welcome feedback and constructive criticism. We are also interested in hearing the stories of people who have taken microcap companies private, whether it worked well or not.

I sincerely appreciate anyone who has made it to the end of this long piece. I will be using this platform to update our subscribers on the progress we make. Thanks a lot for following me on this journey.

About to take the plunge,

Ben Claremon

Very well explained!